A crisis is an event that affects or has the potential to affect the whole of an organisation, such as causing a significant impact on human lives, properties, finances, and/or reputation. Although organisations cannot avert all forms of crisis, they should make appropriate and prior planning and preparation so that they may limit the duration of and damage by major crises.

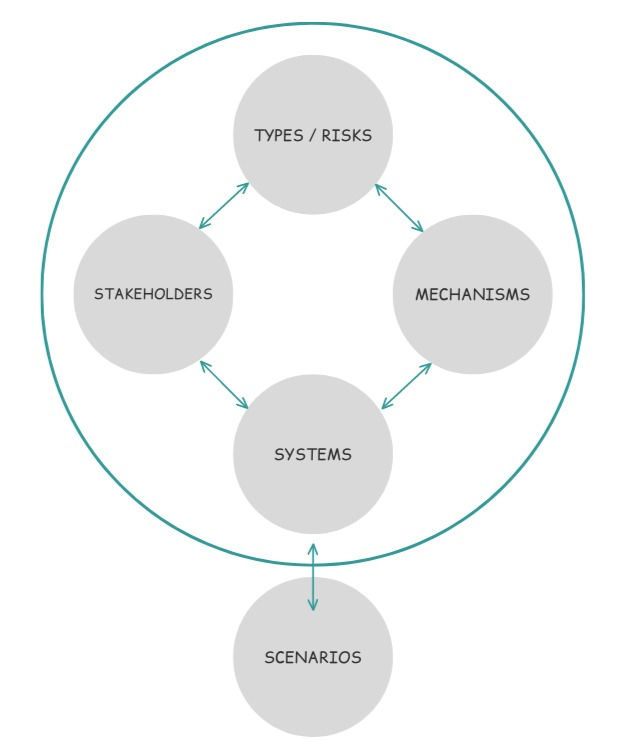

An effective way to achieve this goal is to adopt the Best Practice Model (see Figure 1), which can serve as a benchmark for organisations to measure their existing crisis management performance [1].

Figure 1

Best Practice Model for Crisis Management

This model is characterised by five key elements that should be managed before as well as during and after a major crisis:

(i) Types/Risks

(ii) Mechanisms

(iii) Systems

(iv) Stakeholders

(v) Scenarios

1. Types and Risks of Crises

Research in crisis management suggests that crises can be classified into seven categories or risks that all organisations must be prepared for:

(i) Economic (e.g., Labour strikes; Labour unrest; Labour shortage; Major decline in stock price and fluctuations; Market crash; Decline in major earnings)

(ii) Informational (e.g., Loss of proprietary and confidential information; False information, Tampering with computer records; Loss of critical computer information concerning customers)

(iii) Physical (e.g., Loss of crucial equipment, plants, and material supplies; Breakdowns of crucial equipment or plants; Loss of critical facilities; Major plant disruptions)

(iv) Human Resources (e.g., Loss of key executives or personnel; Rise in absenteeism; Surge in vandalism and accidents)

(v) Reputational (e.g., Slander; Rumours; Gossip; Damage to corporate reputation; Tampering with corporate logos)

(vi) Psychopathic Acts (e.g., Product tampering; Kidnapping; Hostage taking; Terrorism; Workplace violence)

(vii) Natural Disasters (e.g., Earthquake; Fire; Floods; Explosions; Typhoons; Hurricane)

While it may be unrealistic to prepare for every type of crisis in each category, organisations should prepare for at least one crisis in each category to ensure the robustness of their crisis management performance.

2. Mechanisms

Various mechanisms are crucial in planning for and responding to crises before, during, and after their occurrence. These mechanisms can be for predicting, detecting, responding to, containing, learning from, and reshaping organisational practices for managing crises.

For instance, having appropriate signal-detection mechanisms can allow organisations to detect and act on early warning signs to prevent a crisis. To illustrate, a slow but noticeable increase in accident rate at a workplace may be a potential indicator of a looming major accident.

On the other hand, conducting post-mortems of crises and near misses can be an effective mechanism to assess key lessons learned for improving future crisis management performance.

3. Systems

There are also five common and interconnected systems governing and driving organisations’ behaviours that can impact their crisis management performance:

(i) Technology

(ii) Organisational structure

(iii) Human factors

(iv) Culture

(v) Top management psychology

For example, these days, all organisations will possess some form of technology ranging from computers that process critical information and computerised systems for managing services to large plants manufacturing products. Yet, technologies are controlled by humans, who are prone to errors, either intentionally or unintentionally. Hence, as much as possible, these systems should be designed to reduce, if not eradicate, the effects of human errors.

On the other hand, technologies are embedded across the diverse and complex structure of organisations that may engender other kinds of errors, such as hindering correct information from reaching the right person promptly to make the right decisions. In that sense, the operation of technologies is affected by humans and the organisations in which they are embedded.

Furthermore, organisations, like humans, may use different defence mechanisms to refute their vulnerabilities to crises and justify why they do not need to engage in effective crisis management, which constitutes the organisation’s culture of crisis management.

4. Stakeholders

As part of crisis management, organisations must work closely with various internal and external stakeholders, including their employees and external parties like contractors, the police and fire departments. Building solid relationships with stakeholders before a crisis is, therefore, crucial for developing their capabilities to respond effectively to various crises.

5. Scenarios

Finally, developing good crisis scenarios pertinent to the organisation is vital to connect the four elements mentioned above. In other words, a good crisis scenario is a plan for the unthinkable crisis.

For instance, the scenario may entail a particular crisis the organisation has not considered or is unprepared for. The crisis may also occur during peak hours, which may be the worst possible period for the organisation. Similarly, the scenario may comprise the failure of critical systems or a chain reaction of crises occurring simultaneously.

To summarise, the five elements described above represent the benchmark organisations may use to evaluate their crisis management performance. Indeed, it is through asking some of the toughest questions that organisations can identify major weaknesses in their crisis management. After all, effective crisis management eventually boils down to two essential questions:

(i) How much reality can an organisation bear to learn about itself with regard to its crisis strengths and weaknesses?’; and

(ii) How much is an organisation willing to invest in correcting its weaknesses and improving upon its strengths?

Reference

[1] Mitroff, I. I., & Anagnos, G. (2000). Managing crises before they happen: What every executive and manager needs to know about crisis management. American Management Association.

Comments